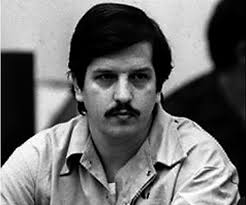

On the night of February 22, 1996, William George Bonin requested two pepperoni and sausage pizzas, three pints of coffee ice cream and three six-packs of Coke for dinner. He watched “Jeopardy” while he ate. Hours later, he put on a new pair of denim pants and a blue work shirt and was led to the execution chamber at San Quentin Prison. At 12:13 a.m. on February 23, 1996, Bonin was pronounced dead, the first inmate executed by lethal injection in the state of California.

Bonin, known as the “Freeway Killer”, was convicted of 14 murders committed across two counties between 1979 and 1980, and he was suspected in many other deaths. His victims were all boys, 12 to 19 years old—some hitchhikers, some prostitutes, some just young men in the wrong place at the worst possible time—who were robbed and raped before being killed and dumped along California freeways. According to court records, most had marks on their wrists and ankles indicating they had been tied up, and some showed signs of beatings and torture. On August 6, 1979, the body of the first victim Bonin would be convicted of killing was discovered naked on the side of a road in Malibu Canyon. Marcus Grabs, a 17-year-old German student on a backpacking trip, was abducted the night before, sodomized, beaten and stabbed 77 times. Weeks later, on August 27, the body of 15-year-old Donald Hyden was found near an off-ramp of the Ventura Freeway. He had been sodomized, stabbed and strangled, and he had a burn mark above his groin. At least a dozen more victims followed, most killed by ligature strangulation. According to court records:

When he was arrested on June 11, 1980, Bonin was caught in the act of raping a 15-year-old boy in his van. Police found white nylon cord and three knives in the vehicle. Bonin later gave investigators a statement leading them to the body of 14-year-old Sean King, who had disappeared from a bus stop in Downey on May 20, 1980, but that statement was not admissible in court. He was acquitted of King’s murder. Court records show Bonin had at least four alleged accomplices during the course of his killing spree. One, Vernon Butts, committed suicide in jail while awaiting trial. Gregory Miley and James Munro, two teens who had sexual relationships with Bonin, pleaded guilty to murder charges and cooperated with the prosecution. According to prosecutors, Gregory Miley was 18 years old when he and Bonin picked up one of the victims, Charles Miranda, near the Starwood Ballroom in West Hollywood in the early hours of February 3, 1980.

Bonin sodomized Miranda and Miley attempted to but was unable to do it. Miley testified that Bonin whispered to him, “This kid’s going to die,” and began to tie him up. He asked why Bonin did not just let Miranda go and Bonin replied, “No, man, he’ll know the van and he’ll know us.” Bonin and Miley then used Miranda’s shirt to suffocate him and crushed his neck with a jack handle, court records state. After they dumped his body in an alley, Bonin said, “I’m horny again. I need another one,” according to Miley. Later that morning in Huntington Beach, they picked up James Macabe, a 12-year-old who said he was on his way to Disneyland, according to prosecutors. Miley drove the van while Bonin sexually assaulted him. The two then strangled Macabe with a shirt and left his body in a dumpster. At Bonin’s Orange County trial, James Munro, who was 18 at the time of Steven Wells’ murder, testified that he and Bonin picked up Wells as he was hitchhiking on the afternoon of June 2, 1980 and brought him to Bonin’s house. According to Munro, Bonin offered to pay Wells if he would let him tie him up during sex. Munro then helped hold Wells down while Bonin strangled him with a t-shirt.

When they were on their way to dispose of the body, they bought cheeseburgers with $10 they took from Wells’ wallet, Munro claimed. As they ate, Bonin allegedly looked up and laughed, saying, “Thanks, Steve, wherever you are.” However, Munro changed his story about exactly what happened many times. Several exhibits introduced at the trial showed inconsistencies, including letters Munro wrote to judges and to Bonin’s defense attorney claiming that he either never saw Bonin kill anyone or that he killed Wells himself. Bonin’s attorney highlighted these contradictions during Munro’s cross-examination. A fourth accomplice, William Pugh, was the one who first put police onto Bonin’s trail, according to court records. After an arrest for unrelated auto theft charges on May 29, 1980, Pugh, then 17, told authorities that he had gotten a ride home from a party with Bonin once and that Bonin talked about having killed young boys. Investigators eventually learned that Pugh participated in Bonin’s March 1980 abduction and killing of Harry Turner. Still, his tip gave police a suspect, and Bonin was placed under surveillance on the night of June 2, leading to his arrest just over a week later, according to a probation officer’s report. Pugh was convicted of voluntary manslaughter in Turner’s death and sentenced to six years in prison.

Once detectives convinced Bonin’s friend and neighbor, Scott Fraser, of his guilt, Fraser told them that Bonin claimed to have killed a teen in self-defense in August 1979 and that Vernon Butts was present at the time, Fraser said Bonin claimed he hid the body because he thought police would never believe him, given his criminal record for assaulting teenage boys. Police then arrested Butts, who confessed to participating in six or seven murders with Bonin before his suicide, investigator John St. John told the Register. Fraser ultimately received a $20,000 reward that had been offered for information in the case. In addition to Fraser, Miley and Munro, another key witness at Bonin’s trials was reporter David Lopez of KNXT in Los Angeles. Lopez, who interviewed Bonin in jail after his arrest, testified that he showed Bonin a list of 21 presumed victims of the Freeway Killer and Bonin admitted to murdering 20 of them.

When Lopez asked what he would be doing if he was not in jail, Bonin said, “I'd still be killing. I couldn't stop killing. It got easier with each victim I did." Prosecutors also presented forensic evidence linking Bonin to several of the murders. Investigators found triskelion-shaped fibers on the bodies of three of the victims that were consistent with the carpeting of his van. Hair that matched Bonin’s was found on three other victims. Also, human blood stains were found in several places in Bonin’s home and vehicle. At both of his trials, Bonin’s defense largely focused on attempting to discredit the prosecution witnesses, many of whom were criminals who stood to benefit from testifying against him. During the penalty phases, they tried to show that Bonin had been abandoned and abused as a child and that he had the potential to behave well and contribute to society in the structured setting of a prison if spared the death penalty.

Bonin’s former pre-parole counselor testified that he seemed interested in helping people and raised money to support the family of a prisoner in New England. A records custodian from Atascadero State Hospital said Bonin volunteered for experimental treatment programs while in custody for a previous sexual assault conviction. Defense experts testified that Bonin suffered from repeated abandonment as a child and that he showed signs of organic brain damage. Dr. Jonathan Pincus said Bonin exhibited a “snout reflex” and a “right Babinski reflex” that suggested frontal lobe damage, which could have made him uncommonly impulse-driven. However, Dr. Park Dietz, testifying for the prosecution, said that Bonin did not present any other behaviors associated with such damage and he testified that the reflexes Pincus observed would not explain a desire to sexually assault young men. Dietz determined that Bonin was a sexual sadist with a possible antisocial personality disorder, but he did not identify signs of any other neurological or psychiatric disorders.

Bonin was sentenced to death in both Los Angeles County and Orange County. An opinion on the case written by Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Alex Kozinski in 1995 highlighted a disturbing truth about Bonin’s crimes: “The facts of this case shock even those of us inured to shocking facts by years of capital cases. Most distressing, however, is that these tragedies could have been averted: Bonin gave us more than fair warning of his proclivities before he embarked on his killing spree.” Testimony by Bonin’s relatives and others at his trial alleged that his father was an abusive alcoholic and that Bonin was sexually abused in a detention home as a child. He served in Vietnam, received a medal for saving a fellow soldier and was honorably discharged, but he also engaged in what a judge described as “violent nonconsensual homosexual activity” during his service. Family members testified that he returned from the war a changed man. According to court testimony, he had planned to marry a woman when he came back, but she married someone else while he was away.

Between 1968 and 1969, Bonin abducted and sexually assaulted four teenage boys. One said he was gagged with his underwear and another was choked nearly to unconsciousness. When he was arrested in 1969, Bonin was driving with a 16-year-old boy. He told police he might have killed the teen if they had not caught him, according to court records. He was committed to Atascadero State Hospital as a “mentally disordered sex offender amenable to treatment.” However, in 1971, he was found unamenable to treatment and sent to prison instead. Bonin was released in 1974 and was convicted of sexually assaulting a teenage boy at gunpoint the following year. At the time of his arrest, he told police he would never leave a witness alive to testify against him again, court records showed. In 1978, he was paroled. A year later, the freeway killings began. Bonin presented numerous arguments in his appeals, many relating to alleged failures by his trial attorney to present mitigating evidence and decisions by judges that he argued infringed on his rights. Appellate courts agreed that some errors were made, but they never concluded that those mistakes—such as allowing David Lopez to testify that Bonin admitted to 20 or 21 murders rather than just 14, or only letting one of his two defense attorneys present closing arguments—would have impacted the verdict.

While awaiting his execution, William Bonin wrote a collection of stories and essays that received a small print run. The book, titled “Doing Time, Stories from the Mind of a Death Row Prisoner,” included several fictional tales of young boys in danger that ended with moments of redemption. “I like the way my writing is going…the message that I’m trying to get across,” Bonin said in a 1991 telephone interview with the paper. On the morning before his execution, while his attorneys filed motions for last-minute intervention by the Supreme Court, Bonin gave an interview to a local radio station. He told a reporter he had accepted the fact that he was going to die. However, he said of the victims’ families, “They feel that my death will bring closure. But that’s not the case. They’re going to find out.” About 50 witnesses attended the execution, including family members of several of Bonin’s victims and the survivor of the 1975 attack.

According to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Bonin delivered his last words to the prison warden 45 minutes before his death. “That I feel the death penalty is not an answer to the problems at hand,” Bonin said. “That I feel it sends the wrong message to the youth of the country. Young people act as they see other people acting instead of as people tell them to act. And I would suggest that when a person has a thought of doing anything serious against the law, that before they did, that they should go to a quiet place and think about it seriously.” Two of Bonin’s accomplices remain in prison today. Gregory Miley, who was sentenced to 25 years to life for first-degree murder, had planned to seek parole in 2011, but he agreed to a continuance until 2014. In apress release announcing the delay, the Orange County District Attorney’s Office noted that Miley had incurred 26 prison rule violations including threats against inmates and nonconsensual sexual behavior that indicated he could pose a “significant” threat to the public if released. James Munro is serving 15 years to life for second-degree murder. At his sentencing hearing, the superior court judge stated, “He should every few seconds say a prayer that he is not going to the gas chamber with Bonin. For what he has done, I would have no problem sending him there, so I think he’s very, very fortunate.” Munro has tried and failed several times to get paroled. Over the last 22 years, he told several different versions of the events surrounding the murder of Bonin’s final victim, Steven Wells, according to court records and parole hearing transcripts.

Munro sometimes claimed that he watched Bonin kill Wells but did not participate at all, and he convinced his wife—who he married while in prison—and other supporters that he was completely innocent. He also sent letters to the district attorney’s office in 1994 and 1998 claiming that he was the one who killed Wells, but he later stated at a 2005 parole hearing that he only did that to “piss off” the prosecutors. When he has admitted to helping Bonin with the crime, Munro insisted that he only did so out of fear that Bonin would kill him if he did not. “I was scared to death,” he said at a 2005 parole hearing. “I was a victim as well as Steven Wells. Steven Wells died. I swear to God, I wish he never had.” Wells’ family has expressed doubt about Munro’s remorse. “I feel that he fully participated in this murder,” his sister, Susan Ruzzamenti, said at a 2009 hearing. “I feel he enjoyed it, and I feel that he received some type of deviant sexual satisfaction from it.” The parole board has repeatedly rejected Munro’s release, citing his history of minimizing his involvement in the crime and psychological evaluations that indicate he may pose a risk to the public. In 2009, the board ruled that Munro could seek parole again in five years. William Bonin continued to spark outrage and controversy even after his death, when it was revealed that the Social Security Administration had continued to pay benefits stemming from a 1972 diagnosis with mental illness into his bank account while he was on death row. Nearly $80,000 in disability checks was deposited in the account during the years between his arrest and execution. Bonin’s family agreed to repay the funds once the error was discovered, the paper reported. An investigation by the Social Security Administration concluded that no other death row inmates were receiving similar benefits.